A Beginner’s Guide to Pandemic

Author

Valerie Jojola-Mount

Graduate Student

Master of Public Health program

Kansas State University

In an unprecedented moment proceeded by a strange series of events, our academic and personal lives have changed. We left on spring break, hopeful for a week of rejuvenation and rest, and, in a matter of days, discovered ourselves not only unable to return to campus, but also living the origin story of many a dystopian novel. Below is an attempt to answer some of the questions budding students of public health may be asked by family, friends, and neighbors. Additionally, I have some entertaining and informational resource recommendations as social distancing practices continue into the late summer and fall months.

Why China?

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel viral infection, meaning it is previously unseen in humans and, therefore, all members of our species are equally susceptible. While it originated in China, it is not a “Chinese issue,” contrary to some lines of anti-Asian sentiment being circulated. The basics of One Health apply: contracting and expressing symptoms of COVID-19 relates to a complicated interaction between agent (severe acute respiratory virus coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2), environment, and host. Not everyone who encounters the pathogen will become infected, and not all who are infected will develop clinical signs and symptoms, though some may still be able to spread the disease to others (i.e. asymptomatic carriers).

|

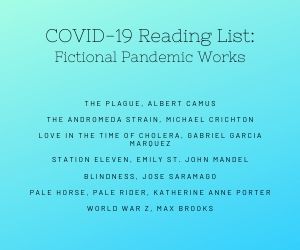

Figure 1. COVID-19 reading list. |

We may find ourselves wondering why this disease emerged from China. The short answer is globalization. The long answer involves some background knowledge of China’s history. For much of the 20th century, China experienced political and social unrest, exacerbated by famines. In an effort to help citizens feed and provide for themselves, the country enabled wildlife husbandry, or the cultivation, breeding, and sale of wildlife for consumption and profit (Ellis, 2020). At wet markets, products of this husbandry were sold, which became a perfect intersection for pathogen transmission. Wildlife such as bats, pangolins, and civets—and all their unique diseases—were in close proximity to and eaten by people throughout Asia (Ellis, 2020). Even though the country is no longer in the same state of nutritional instability, the wet markets have remained, thus enabling this intersection with the added components of greater population size and easier travel: globalization.

I highly recommend watching an episode of Explained on Netflix entitled, “The Next Pandemic,” which describes the socio-historical context of China and its emerging diseases.

Why was COVID-19 not detected sooner? Can we compare it to the flu?

From an epidemiological perspective, the identification of COVID-19 was relatively rapid; implementing key practices and communicating with the public in a cohesive manner has been more problematic. Identified as unusual by Chinese doctors, public health workers quickly traced COVID-19 to a specific wet market in Wuhan (World Health Organization, 2020). While Chinese authorities stated whistle blower, Li Wenliang, started spreading rumors unnecessarily about a novel disease, they nevertheless alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) on December 31, 2019, of a peculiar viral pathology (WHO, 2020).

COVID-19 behaves differently than the influenza virus and other previous coronaviruses like SARS and MERS. Although the spread of COVID-19 shares certain characteristics with the historical, large-scale transmission of the flu, it is in a class of its own. It is less virulent than SARS and MERS; it is less infectious than measles but somewhat more so than a common cold; its pathogenicity seems to vary by age class (Cascella, Rajnik, Cuomo, Dulebohn, & DiNapoli, 2020). It also appears to have a high percentage of asymptomatic carriers and a long period of infectivity prior to symptomatic onset, making it more of a struggle to contain than a disease like smallpox.

In line with the previously mentioned episode, Coronavirus, Explained is entirely focused on SARS-CoV-2 in its episode entitled This Pandemic, currently available on Netflix.

What about a vaccine?

Vaccines are complicated and sometimes hard to develop. They are probably the safest treatments available because they are prophylactic and, therefore, given to otherwise healthy individuals. Vaccines can be hard to access because they must be stringently tested before they can be considered for market. On average, non-seasonal flu vaccine research takes 10-15 years to reach phase IV clinical trials for human treatments, primarily because their research and testing standards are so heavily regulated (Milligan & Barrett, 2015).

One potential hurdle to the development of a vaccine is genomic sequencing of the causative agent. Thankfully, this hurdle was surmounted back in January by Chinese researchers who sequenced SARS-CoV-2 early on, eliminating costly delays and enabling the quick progression of COVID-19 vaccines to human trials. Struggles remain, however, in the form of production. Even when researchers find a widely effective vaccine in the coming months, the prospect of creating enough for the entire nation will be challenging. Additionally, vaccine hesitancy will further complicate the road to herd immunity.

Vaccines are a hot movie topic, appearing in feature-films like Outbreak and Contagion. Numerous documentaries also discuss this issue, usually in the context of hesitancy surrounding their administration to children. Frontline’s “Vaccine War” is dated (from 2010) but informative of common concerns regarding vaccines, as is “Vaccines—Calling the Shots” from NOVA.

If you find yourself in a truly existential rut while sheltering in place, I would recommend one last source for you: The Plague by Albert Camus. Potentially one of the most critical novels of the twentieth century, The Plague is eerily vital for our times. Camus reminds us that life is fleeting and suffering indiscriminate, but basic acts of humanity can cultivate enough purpose and love to guide us—even as incidence and case fatality rates soar.

Figure 2. A list of fictional works about various pandemics.

References

Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., et al. (2020). Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19) In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/

Ellis, S. (2020, March 6). Why new diseases keep appearing in China. Available from https://www.vox.com/videos/2020/3/6/21168006/coronavirus-covid19-china-pandemic

Milligan, G. & Barrett, A. (Eds). (2015). Vaccinology: an essential guide. Oxford, UK: Wiley & Sons Ltd.

WHO. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) events as they happen. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

Next Story: Fighting the Spread of Disease With…Words?

One Health Newsletter

The One Health Newsletter is a collaborative effort by a diverse group of scientists and health professionals committed to promoting One Health. This newsletter was created to lend support to the One Health Initiative and is dedicated to enhancing the integration of animal, human, and environmental health for the benefit of all by demonstrating One Health in practice.

To submit comments or future article suggestions, please contact any of the editorial board members below.