One Health Newsletter

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic in Washington, District of Colombia

Author

Julia Leas

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, and the subsequent Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), pose a severe, persistent, complex, but treatable issue for most individuals globally. Currently, there are over 40 million HIV-positive people around the world, with the highest population prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of all people living with HIV reside.1 However, HIV affects developing countries as well as industrialized nations. In the United States, approximately 1.2 million people live with HIV, with rates varying greatly between and within states.1 HIV disproportionately affects Black populations, lower-income individuals, and the LGBTQIA+ community.1

The fight against HIV and AIDS has always been part of the One Health approach. Human science, social science, political science, and the health sector converge and collaborate to ensure the effectiveness of actions taken against this deadly pandemic.

Washington, District of Columbia (DC) serves as a microcosm of the global HIV epidemic, highlighting the disparities which define and perpetuate this disease. The prevalence of HIV in DC sits at 1.8% of the total population, with 11,904 residents currently living with the virus.2 This 2022 HIV prevalence percentage puts DC on par with countries such as Cote d’Ivoire, Tongo, Haiti, Gambia, and Ghana in the fight against HIV.1 The current picture of HIV in DC shows how the outbreak is stratified along gender, racial, social, and geographic lines. Looking at the 2020 incidence of HIV in DC, 80.8% of new diagnoses are males, 71.7% are Black, and a majority of these cases occur in the city’s Southeast wards.3 Considering the broader demographic makeup of the district, 47.5% male, 45.8% Black, and relatively equal population sizes among the eight wards, a clear problem emerges in the handling of this epidemic throughout DC, as Black Men, Latino Men, White Men, and Black Women are still experiencing HIV at epidemic levels.2

Methods

This article looks at the interaction of populations, regulations, and demographics on HIV outcomes. The presented case study focuses on Washington, DC, looking at the geography and social heterogeneity of its population. DC does not have any legislation criminalizing HIV exposure or transmission, only maintaining laws around consent, testing, reporting, and confidentiality. DC requires minors’ autonomous consent to Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) services and provides anonymous HIV testing to the general population. Reporting standards require all providers to submit a comprehensive report of all HIV cases to the DC Department of Health (DoH). The confidentiality of medical records and information is legally ensured, as identifying information may only be disclosed to safeguard the physical health of others. Altogether, DC provides a positive approach in terms of HIV legislation with uniform consent, testing, reporting, and confidentiality standards. Geographically, DC is divided into eight wards, each ward containing a relatively equal population size (Table 1).3,4

Table 1: HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, and the demographic factors of race, socioeconomic status, and education level for the District of Columbia in 2023 broken down by geographic ward.

DC Total

1.80%

n/a

37.30%, 45.80%, 11.50%

$102,806, 10.52%

8.37%

DC Ward

Prevalence Rate (2020)

Incidence Rate (2016-2020)

Race (1)

SES (2)

Education (3)

Ward 1 (NW)

1.52%

0.14%

58.99%, 20.90%, 20.74%

$122,077, 9.03%

9.24%

Ward 2 (NW)

1.18%

0.10%

69.52%, 13.09%, 12.09%

$126,596, 4.50%

4.27%

Ward 3 (NW)

0.31%

0.04%

81.42%, 5.26%, 9.54%

$155,813, 1.63%

2.30%

Ward 4 (NW/NE)

1.27%

0.18%

32%, 45.11%, 25.75%

$108,810, 5.72%

11.79%

Ward 5 (NE)

1.68%

0.23%

31.93%, 54.53%, 11.74%

$104,296, 6.81%

8.93%

Ward 6 (central)

0.95%

0.10%

49.89%, 38.4%, 8.37%

$128,791, 7.37%

6.49%

Ward 7 (SE)

2.69%

0.31%

3.19%, 91.49%, 4.26%

$50,130, 21.53%

12.61%

Ward 8 (SE)

2.29%

0.28%

4.38%, 91.61%, 3.13%

$44,665, 23.35%

12.85%

Legend: The table shows the demographic breakdown of each ward by race, socioeconomic status (SES), and education level, in addition to the HIV Prevalence (2020) and Incidence (2016-2020) rate within each ward

Caption: 1= White, Black, Hispanic/Latino; 2 = Median household income, Percent of families below the poverty line; 3= Percent of residents aged 25+ with less than a HS GraduationSource: Adapted from Sullivan et al., 2020; DCHMC, 2023

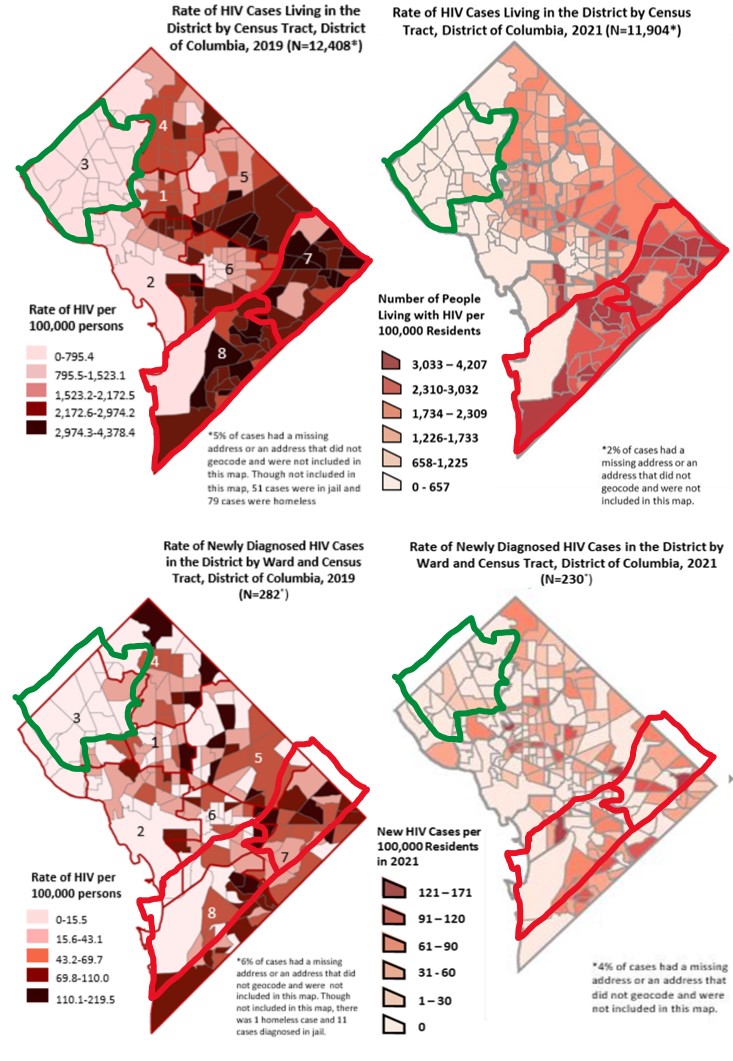

By comparing Wards 3, 7, and 8, it illuminates the racial, socioeconomic, and educational disparities driving the HIV Epidemic in DC. Ward 3, situated in the Northwest section of DC, has the lowest HIV prevalence and incidence rates, corresponding with the highest population of White residents, higher incomes, and educational attainment. Contrast that with Wards 7 and 8, situated oppositely in the Southeast portion of DC, which have the highest prevalence and incidence rates of HIV, corresponding with the highest populations of Black residents, lowest incomes, and educational attainment levels (Fig.1). DC has a nationally recognized system of healthcare, but six out of the system’s seven hospitals are in Northwest DC, leaving only one hospital to serve all the residents living in the Eastern wards. The significantly higher prevalence and incidence of HIV infection, and lower levels of viral suppression, persisting among the most underserved and marginalized communities show how health inequity underpins DC’s HIV Epidemic.2

Results and public health strategies

To address this epidemic, DC launched two major HIV prevention programs.

The Phase I program (2016) was the “90/90/90/50 Plan” to end the HIV Epidemic in the District of Columbia by 2020.5 The name highlights the program’s goals: 90% of HIV-positive district residents know their status; 90% diagnosed with HIV are in treatment; 90% diagnosed with HIV in treatment are reaching viral load suppression; 50% reduction in new HIV infections.5 The key strategies focus on data-to-care, linkage, re-engagement, and retention, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and rapid antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation.5

Phase II program (2020) following the “90/90/90/50 Plan”, named “DC Ends HIV,” maintains the vision of “ending the HIV epidemic and supporting the best, most equitable health outcomes for all communities in DC,” with a guided mission of “providing prevention and treatment services …. responsive to the well-being and needs of communities and individuals.”6 The “90/90/90/50 Plan” builds upon the previous testing, treatment, and viral suppression targets, as well as highlights broader goals that align with these updated targets: to have < 21 new diagnoses of HIV a year by 2023, ensure people living with HIV can easily and safely maintain optimal integrated health, and to collectively acknowledge - and actively address - the impact of stigma and structural racism on sexual health and HIV outcomes.6 Altogether, the strategies being deployed to reach these goals focus on HIV testing, PrEP and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), rapid ART, Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U) messaging, data-to-prevention, harm reduction, wellness services, and molecular surveillance.7

Although well-intentioned, the “DC Ends HIV” plan still demonstrated geographic and social health disparities of HIV rates between the various DC wards (Fig.1).2

Figure 1. Change in HIV Prevalence Rates (top) and Incidence Rates (bottom) in the District of Columbia from 2019 (left) to 2021 (right) broken down by geographic ward.Open Source: District of Columbia Department of Health, 2020 & 2022; https://dchealth.dc.gov/service/hiv-reports-and-publications

Black residents, who primarily reside in wards 7 and 8, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community receive the greatest share of new HIV cases. Although Black residents only make up 45% of DC’s population, they account for 71% of all known HIV cases in the district.2 Over the last five years, there has been a 42% decline in newly diagnosed cases of HIV for White people and a 37% decline for Hispanic/Latino people, yet only a 24% decrease for Black individuals;2 in DC, one out of every two new HIV diagnoses are Black men; 2 35% of all new cases are Black Men who have sex with other Men (MSM);2 eight in 10 newly diagnosed women are Black.2 This racialized trend continues once HIV-positive residents engage in care, with 95% of White individuals hitting viral suppression levels, but only 72% of Black individuals reaching viral suppression, a key element of HIV treatment and transmission reduction.2

Moving Forward

Key Components of Prevention Programs. These persistent disparities highlight the need to address the systemic flaws baked into the “DC Ends HIV” program to control the HIV Epidemic in DC once and for all. The four pillars of HIV prevention programs are early diagnosis, rapid treatment to viral suppression, prevention for high-risk individuals, and swift detection/response to emerging clusters.7 Additionally, there are nine characteristics consistently associated with effective prevention programs: comprehensive approaches, varied teaching methods, sufficient dosages, theory-driven, fosters positive relationships, appropriate timing, sociocultural relevance, outcome evaluations, and well-trained staffs. Ultimately, improvement is ensured by administering rapid HIV treatment to sustain viral suppression levels, which can be achieved through sufficient ART dosages via sociocultural relevant messaging and competent care tailored to high-risk populations.

Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U). U=U messaging is crucial moving forward because it dually utilizes ART as a method of treatment and prevention. It is proven that HIV-positive individuals using ART to reach undetectable viral loads (i.e., viral suppression) cannot sexually transmit the virus.8 This U=U message is therefore important to spread in order to show the regression of the disease and remove guilt surrounding the virus as individual health is preserved and a transmission pathway is eliminated. Ultimately, this message serves to educate the population and eliminate the stigma of HIV.

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP). PrEP and PEP medications need to be readily available to high-risk populations by culturally tailoring treatment messaging towards such populations. Having providers who match the gender, racial, and sexual identities of patients is proven to increase the uptake of HIV treatments. Offering PrEP and PEP counseling with culturally competent providers to young Black MSMs, significantly increased the uptake of these treatments by groups historically difficult to engage. The “DC Ends HIV" program must focus on providing culturally competent care that targets, but does not stigmatize, high-risk populations.

Conclusion

Health inequity encapsulates the state of HIV in DC, as various programs have repeatedly failed to address the foundational racial and socioeconomic dynamics driving this epidemic. With HIV rates nearly zero in the highly affluent Ward 3, which is 80% White, and HIV rates comparable to those of Cameroon and the Central African Republic in the least affluent Wards 7 and 8, which are 91% Black, a clear pattern of inequitable health care emerges.1,4 The local regulations surrounding HIV are sound, so it is necessary to address the programs themselves to facilitate equitable improvements in DC’s HIV response.

The current “DC Ends HIV” program needs to improve the availability and accessibility of its HIV prevention resources (i.e., prevention and treatments) in the district’s most underserved communities to end this epidemic. This progress can be enhanced by implementing culturally competent U=U messaging and engagement with existing local grassroots organizations in Wards 7 and 8 to increase program participation. A commitment to expanding HIV funding, resources, and care especially in high-risk populations in eastern DC as well as building trust in those communities through compassionate collaboration appears necessary for DC to end HIV.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the professors Dr. Jean-Paul Gonzalez and Dr. Richard Calderone and who guided and supported me in my studies at the Georgetown University, Biomedical Science Policy and Advocacy (BSPA) Program.

References

-

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HIV Basics Overview: Data & Trends, U.S. Statistics and Global Statistics. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/#. Updated 2022. Accessed May 21, 2023.

-

District of Columbia Department of Health HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Administration. Annual epidemiology & surveillance report: data through December 2019 and 2021. DC Health; 2020, 2022. https://dchealth.dc.gov/service/hiv-reports-and-publications

-

Sullivan PS, Woodyatt C, Koski C, et al. A data visualization and dissemination resource to support HIV prevention and care at the local level: analysis and uses of the AIDSVu public data resource. Journal of medical Internet research. 2020;22(10):e23173.

-

DC Health Matters Collaborative. Demographics District of Columbia. https://www.dchealthmatters.org/?module=demographicdata&controller=index&action=index&id=130951§ionId=. Accessed March 2023. Accessed May 21, 2023.

-

Bowser M. 90/90/90/50 plan: ending the HIV epidemic in the District of Columbia by 2020. DC Health; 2016. https://dchealth.dc.gov/page/ending-epidemic-district-columbia-2020

-

District of Columbia Department of Health. DC Ends HIV Plan. https://www.dcendshiv.org/ Updated 2020. Accessed May 21, 2023.

-

Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844-845.

-

Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection: Undetectable equals untransmittable. JAMA. 2019;321(5):451-452.

Next story: Anna Pees’ Journey Involving Interdisciplinarity, Veterinary Regulation, and Multiple ‘Wildcat’ Institutions

One Health Newsletter

The One Health Newsletter is a collaborative effort by a diverse group of scientists and health professionals committed to promoting One Health. This newsletter was created to lend support to the One Health Initiative and is dedicated to enhancing the integration of animal, human, and environmental health for the benefit of all by demonstrating One Health in practice.

To submit comments or future article suggestions, please contact any of the editorial board members.