Advancing Legislation on ‘One Health’ in the United States of America

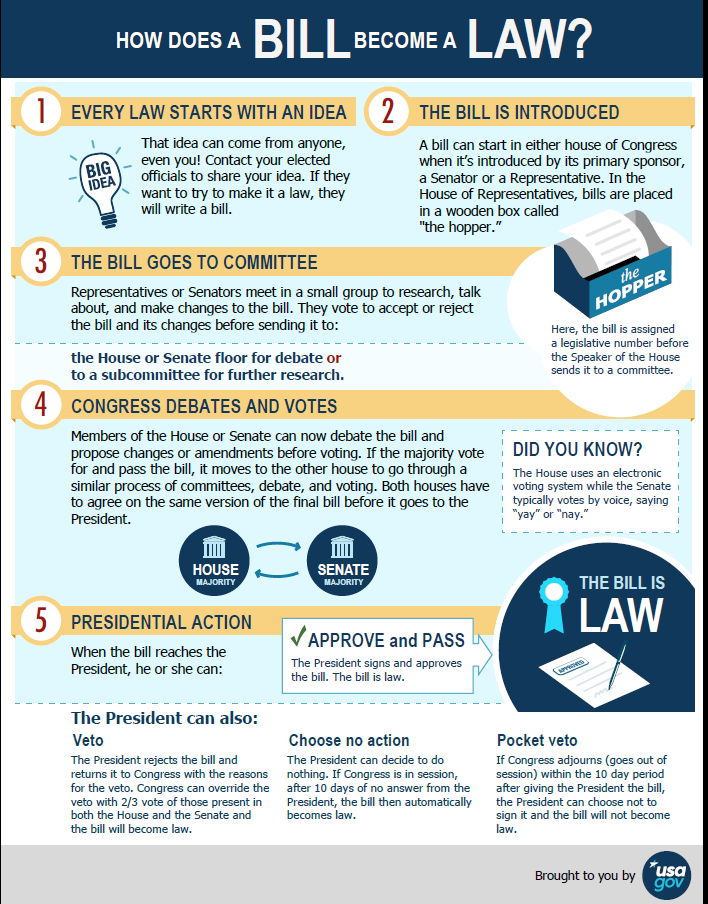

Figure 1. How Does a Bill Become a Law? (Source: https://www.usa.gov/how-laws-are-made#item-213608 and https://www.usa.gov/bill-law-lesson-plan). Figure 2. US Capitol Building. (Source: Bing Free Clip Art).

- Introduction of Legislation – There are four types of legislation: bills, joint resolutions, concurrent resolutions, and simple resolutions. Bills are used to create public policy and resolutions are used to appropriate money or to express a sentiment of Congress. The ideas for bills can come from anyone, although only a Member of Congress can introduce a bill. All bills are assigned an identifying number to designate whether it comes from the House (H.R.#) or the Senate (S.#). If a bill will appropriate money, it must originate in the House.

- Committee Action – Once a bill is introduced, it is referred to the committee that has jurisdiction over its subject. A bill may be sent to a single committee, several committees at once, from one committee to another, or different parts of a bill may be sent to different committees. Most of the work done on a bill takes place at the committee level so committees have significant power to decide which bills will receive the most attention. The more support a bill has, especially from congressional or committee leadership, or from the President, the greater its chance of receiving consideration.

- Subcommittee Action – Following receipt of a bill, a committee will generally refer it to the proper subcommittee, as it has a more specific focus. There are three steps that take place next:

- Hearings: Witnesses are called to testify about the merits or shortcomings of a bill.

- Mark Up: Committee members may offer their own views on a bill and suggest amendments.

- Reporting Out: When the mark up is complete, a final draft of the bill is voted on for approval. If a majority supports the bill, then it is “reported out”. However, if the bill does not receive majority support, then the bill dies.

- Publication of a Written Report – After a committee votes to report a bill, the committee chair instructs the committee staff to prepare a report on the bill. This report describes the intent of the bill, its impact on existing laws and programs, and views of dissenting members.

- Floor Action – The bill is next placed on the House or Senate calendar for debate by the full chamber.

In the House, the Rules Committee sets the terms of debate. This Committee may place limits on the time or debate or on the number and type of amendments that may be offered. If the Committee does not place a rule on a bill, then there is little chance of it being debated, and the bill dies. Once a bill comes to the floor, supporters, and opponents are given a chance to speak. Any amendments offered on the floor must be related to the main subject of the bill.

The Senate places fewer restrictions on debate. The terms of debate are often set by Unanimous Consent Agreement, which is approved by party leaders. Any Senator may filibuster (i.e. delay a vote by using unlimited debate) a bill. A filibuster may only be ended by involving cloture (i.e. 60 Senators must vote in favor to end debate and invoke cloture. Once cloture is invoked, there can be 30 more hours of debate). When debate concludes in either chamber, a vote can take place to approve or defeat a bill. - Conference Committee – Bills may originate in one chamber, and upon passage, move to the opposite chamber to repeat the approval process. Often, however, similar bills work their way through both the House and the Senate at the same time. Both chambers must pass identical bills in order for the bill to be sent to the President for approval, so the House and Senate will often form a conference committee to reconcile any differences between their bills. Both chambers may instruct their conferees on acceptable compromises. Once the differences are resolved and a conference report is generated, both chambers must once again vote to approve the bill.

- Action by the President – The President has four choices upon receiving a bill:

- Sign the bill into law.

- Veto the bill and send it back to Congress with suggestions for reconsideration. (Note: If the President vetoes a bill, Congress may override the decision. A two-thirds majority vote in both chambers is required to overturn a veto).

- Take no action while Congress is in session, in which case the bill will become law in ten days.

- Take no action and let the bill die after Congress has adjourned for the session. This is called a “pocket veto.”

Grassroots Efforts – To have success in bringing an idea for a piece of legislation forward, there is a need of broad public awareness, recognition, and understanding a specific issue that warrants support by Members of Congress. As former Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives Tip O'Neill stated, “all politics is local”, which encapsulates the principle that the success of politicians is directly tied to their ability to understand and influence the issues of their constituents. Bipartisan [involves the agreement or cooperation between the Democratic (D) party and the Republican (R) party] issues are by far the easiest to rally support around; however, there still needs to be clarity behind why an issue is being taken to Congress and what you want to achieve.

Figure 3. Examples of Grassroots Campaign Logos. (Sources: https://gawtp.com/http://grassrootscampaigns.com/ and https://themoa.org/aws/MOA/pt/sp/advocacy_g). |

One Health Concept and Principle Emerge in the Political Scene and Language

During the second session of the 114th Congress, Senator Al Franken (D-MN) introduced the One Health Act of 2016 (S.2634) on March 3, 2016, to establish a coordinated national plan to fight diseases that come from animal sources such as Zika and Ebola. The One Health Act of 2016 would task the nation’s regulatory agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), to work together to understand, prevent, and respond to animal disease outbreaks. Senator Franken understood how important it was to embrace a One Health approach to zoonotic diseases; however, there was very little time left to gather co-sponsors, and the bill died at the end of the 114th Congress. Moreover, Senator Franken resigned from Congress on December 7, 2017.

Fortunately , U.S. Senators Tina Smith (D-MN) and Todd Young (R-IN), in a bipartisan effort, continued to advance a One Health approach by introducing the Advancing Emergency Preparedness Through One Health Act (S.2615) on March 22, 2018 in the second session of the 115th Congress. The bill was assigned to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pension (HELP). S.2615 focused on improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the U.S. Government’s response to emergencies by requiring the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Service (DHHS) and Agriculture (USDA) to do more that just coordinate, but also actively lead interdisciplinary collaborative efforts with other relevant Departments and Agencies to develop and implement a federal One Health framework for emergency preparedness.

The idea was brought forward, and two Senators stepped up to introduce the legislation; however, they did not have any additional Members of Congress join them as co-sponsors when they introduced the bill. This meant that significant groundwork had to be covered to reach out to Members and their staff to let them know what S.2615 was all about and more importantly, to help them understand what a One Health approach meant in terms of emergency preparedness. Accompanying letters-to-the-editor of major newspapers and Op Eds (i.e., Opposite Editorial page pieces) may also be useful tools to raise awareness of an issue or in this case, S.2615. Regrettably, this did not happen relative to either S.2634 in the 114th Congress nor S.2615 in the 115th Congress.

As noted previously, opportunities for constituents to meet with their Members of Congress when they are back home in their districts is an effective ‘Grassroots’ way to enlighten them about issues of importance and to encourage them to support specific bills that have been introduced. Members of Congress are far more likely to respond to messages that come from their constituents. Face-to-face meetings, phone calls, e-mails, faxes, and letters are great ways to communicate your message.

In addition to individual outreach, forming coalitions of interested parties can go a long way to demonstrate support for a bill. When diverse groups concur on an issue it makes it so much easier for the Members of Congress to consider supporting the issue as well. It is also important to know if there is any opposition to a bill or to specific sections of a bill so that Members of Congress are fully informed so that options can be addressed as early in the process as possible to enable the bill to move forward. Being prepared to answer questions or provide additional information to the Members and their staff is quintessential. Telling a ‘story’ to explain the issue is an easy way to help people understand the ramifications of an issue, including the pros and cons.

Figure 4. Volunteering. (Source: Bing Free Clip Art). |

Sometimes, getting a bill through Congress is all about timing. Moving a bill forward as a stand-alone is challenging (see all of the steps outlined above in How Laws are Made). Hence, many times people will look at what other pieces of legislation are moving forward to see whether they can amend all or part of their legislation. Such was the case for S.2615*. The key piece of legislation that was moving through Congress was the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2018 (H.R. 6378). It was passed by the House on September 25, 2018 and sent to the Senate on September 26, 2018 with a new title “H.R.6378 - To reauthorize certain programs under the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act” .

By way of example, some of the verbiage from S.2615 (underlined below) was incorporated into H.R.6378. Under Title 1 – Strengthening the National Health Security Strategy, the following text was adopted: “(9) ZOONOTIC DISEASE, FOOD, AND AGRICULTURE.—Improving coordination among Federal, State, local, tribal, and territorial entities (including through consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture) to prevent, detect, and respond to outbreaks of plant or animal disease (including zoonotic disease) that could compromise national security resulting from a deliberate attack, a naturally occurring threat, the intentional adulteration of food, or other public health threats, taking into account interactions between animal health, human health, and animals' and humans' shared environment as directly related to public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities, as applicable.”

|

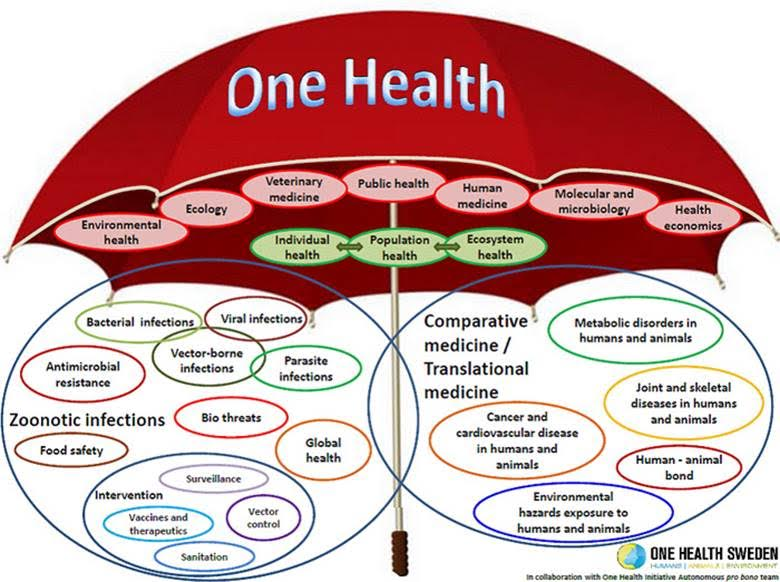

Figure 5. One Health Umbrella. (Source: http://onehealthinitiative.com/about.php). |

At the time of this writing the legislation is still waiting for final Senate approval and passage forward to the President in order to become law.

[*Important complimentary actions to help advance this legislative endeavor were taken by USA One Health advocates in the respective announcement:]

Lessons Learned

The most important lesson learned following the introduction of S.2615 was that there are still many Members of Congress, along with many staff members, who are unaware of the term “One Health” or who do not understand why a multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary “One Health approach” is essential for emergency preparedness. A successful educational campaign about One Health could really go a long way to easing the passage of future legislation that embraces One Health. Therefore, we urge all interested parties to step up and help educate others about One Health and make it a win-win across the board.

What Can You Do To Make A Difference?

- You can be the agent of change. Seek to understand, then reach out to other disciplines to “bring the needed expertise to the table” in a collaborative effort to address the needs more efficiently, and often with an innovative approach not previously considered.

- Engage policy/law makers from your local community, state, and federal levels to embrace a One Health collaborative, multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary approach to issues of mutual concern. Tell a “story” and provide examples of a One Health approach.

- Tell a story that your neighbors can relate to when explaining what is meant by One Health. Small steps really do make a difference! Make it personal and not overwhelming.

- Help facilitate introductions electronically, by phone, or in-person meetings, build relationships, and engage in direct conversations. These steps can lead to action items that embrace a multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary One Health approach.

See pertinent USA applicable One Health reference materials:

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html

One Health Commission https://www.onehealthcommission.org/

One Health Initiative http://www.onehealthinitiative.com/

American Association of Public Health Physicians https://www.aaphp.org/OneHealth

American Veterinary Medical Association https://www.avma.org/KB/Policies/Pages/One-Health.aspx

American Veterinary Epidemiology Society http://www.avesociety.org/

Authors

Bernadette Dunham, D.V.M., Ph.D., Dipl. AVES (Hon.)

Professorial Lecturer

Environmental and Occupational Health

Milken Institute School of Public Health

George Washington University

950 New Hampshire Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20052

Cell Phone: 202-288-9833

E-mail: bdunham@gwu.edu

Internet: http://publichealth.gwu.edu/

Bruce Kaplan, DVM, Dipl. AVES (Hon.)

Contents Manager/Editor, One Health Initiative website

Co-Founder, One Health Initiative team/website

4748 Hamlets Grove Drive

Sarasota, Florida 34235

https://goo.gl/zbVw2t

E-mail: bkapdvm@verizon.net

Phone/fax: 941-351-5014

www.onehealthinitiative.com

One Health Initiative Autonomous pro bono Team:

Laura H. Kahn, MD, MPH, MPP ▪ Bruce Kaplan, DVM ▪

Thomas P. Monath, MD ▪ Lisa A. Conti, DVM, MPH

https://goo.gl/rs7MjP

and Thomas M. Yuill, PhD, manager ProMED Outbreaks Report

http://www.onehealthinitiative.com/promed.php

One Health Newsletter

The One Health Newsletter is a collaborative effort by a diverse group of scientists and health professionals committed to promoting One Health. This newsletter was created to lend support to the One Health Initiative and is dedicated to enhancing the integration of animal, human, and environmental health for the benefit of all by demonstrating One Health in practice.

To submit comments or future article suggestions, please contact any of the editorial board members.