Dr. Robert Cope, DVM 1975

Tribute to a great man: Veterinarian Dr. Robert Cope's death felt across Lemhi County

On Dec. 28, 2022, Idaho lost a good friend. He lost his battle with cancer, but kept doing

what he loved—assisting ranchers—until the very end.

Known simply as “Cope” to friends and clients, Dr. Robert Cope was the main cattle

veterinarian in Lemhi County, Idaho, for 44 years. He also spent 20 years in public

service to his community during that time and to agriculture in Idaho and the West. He

was inducted into the Eastern Idaho Agricultural Hall of Fame on March 18, 2022.

Dr. Cope was born Jan. 12, 1951, in Topeka, Kansas, and grew up on a farm. He planned to

become a Navy officer and was a National Merit finalist and Presidential Scholar in 1969.

Becoming a veterinarian in a small rural community was not on his list!

He was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy, but because of a badly injured knee

(playing basketball his senior year of high school) was unable to physically qualify for the

Navy. So he went to Kansas State University and received a Bachelor of Science degree

in 1973 and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine in 1975.

His knee was considered too bad to stand on a ship, but he spent the next 45 years

wrestling 1,500-pound animals. He worked briefly for a veterinarian in Bowman, North

Dakota, until he saw an ad in the American Veterinary Association Journal for a practice

in Idaho that was for sale.

Dr. Robert Cope tubes a young horse with mineral oil to relieve an impaction. Dr. Cope was the main cattle veterinarian in Lemhi County, Idaho, for more than four decades before his death on Dec. 28, 2022. (All photos on this page courtesy of Heather Smith Thomas)

He drove to Salmon, Idaho, in October 1977. He later told friends: “The opening line of

John Denver’s ‘Rocky Mountain High’ says it all: ‘He was born in the summer of his 27th

year, coming home to a place he’d never been before.’ That’s what happened to me! And

Lou Gehrig was wrong. He said he was the luckiest man on the face of the earth, but I

was that luckiest man. I wandered in here and found my true home. I was able to spend

44 years doing what I loved, with the people I loved, and where I loved doing it. I’ve lived

a life that other men could only dream of!”

He purchased the Blue Cross Veterinary Clinic in November 1977 and started making

ranch calls all over the county. Merry Logan worked at the clinic for a short time in those

early years.

“Working with Cope, I soon learned that he was one of the smartest and kindest people

I’d ever met in my life,” Logan said. “Then in later years I’ve been grateful to him for the

work he did with federal lands issues.”

Logan continued: “He was a county commissioner for many years, and worked on federal

lands committees. When wolves became a problem in 1994 (one of them killed a calf

here, a few days after being released, and wolf advocates claimed the calf was born

dead), he immediately became involved scientifically, and proved the ranchers were

right.”

Dr. Robert Cope, right, reads an ultrasound while someone else operates the ultrasound probe on a cow.

He also helped and supported young people in the community. He didn’t have kids of his

own but he loved kids.

“He was always looking for an opportunity to teach them,” Logan said. “If one of their 4-H

animals got sick or had a problem at the fair, he always helped, and could explain things

so well.”

Chris French grew up on his parents’ ranch near Salmon and remembers Cope coming

multiple times to take care of cattle problems.

“He supported the youth in this county, purchasing 4-H projects at the fat stock sale at the

fair each year,” French said. “My parents were very strict about the money from our 4-H

calves. It went into a college fund. Cope was investing in the next generation; when we

got ready to go to college, most of it was paid for with money we’d saved over the years.”

He bought numerous animals each year; there were many ranch families he helped.

“Cope told me a long time ago why he didn’t have any kids. He chose not to, when he

was in vet school,” French said. “He knew he could either dedicate his life to a family or

to a career helping agricultural families. His rancher clients became his family. … He told

me that because of choices he made—not spending money on himself—he could hold

down the costs of his services. He didn’t have a family to raise or spend time with and

was able to charge reasonable prices.”

He wanted his clients to be able to make a living and be able to pay for his services.

“Now that Cope is gone, and even during this past year when he was unable to come to

the ranch to pull a calf or treat a large animal, whenever we had to call another vet, the

cost was dramatically higher,” French said.

Phil Moulton, a rancher on Wimpy Creek, said Dr. Cope has always been selfless and

accommodating.

“He reminds me of the James Herriot stories. He’d do anything to help you, even if in the

middle of the night and nasty weather, and his fees have always been reasonable,”

Moulton said. “Last year he told me the ranchers of the Lemhi Valley have been his

family. He said his father passed away when he wasn’t very old; he didn’t have much

family. He loved and appreciated the ranchers, and we loved and appreciated him.”

Michael Thomas, who grew up on his parents’ ranch on Withington Creek has a few

cattle as well as a custom fencing business, but for many years he and his wife had a

large ranching operation with several leased places.

“Cope helped us many times, but he was also a friend,” Thomas said. “Unlike some of the

younger vets today, I think Cope cared even more about the people than the animals—

and he did care about the animals. The thing that separated him from other vets today is

that he’d come out at 30 below zero to do a C-section in the middle of the night.”

Thomas said Dr. Cope would do whatever he could to bring down the cost for his customers.

“He drove an old two-wheel drive Ford pickup for years, and everything he did was to

save his clients money. He made a lot of personal sacrifices to help his clients,” Thomas

said. “He once said that if his clients couldn’t succeed and be sustainable, he wouldn’t

have a practice, so he kept his prices low. And he never refused to come out on a ranch

call. The only time he ever had to tell us he couldn’t come was when he was in

Washington, D.C. (probably working on some political effort to help rural western

agriculture) and it was physically impossible. But he’d still give advice over the phone and

never charged anyone for advice.”

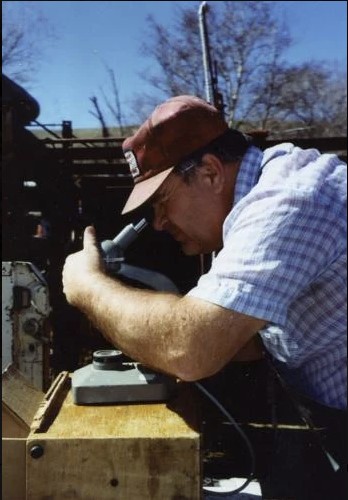

A younger Dr. Robert Cope looks at bull sperm under a microscope.

Dr. Cope had a lot of practical knowledge because he had so much experience with all kinds

of animals and could probably remember everything he learned in vet school and

afterward, including things he read about or heard of. He was never afraid to suggest

something to try. With him gone, it’s like the library burned down; he had such a wealth of

knowledge and advice he shared with clients.

Dr. Cope had many friends since he was very involved in local, regional, state and federal

government. Steve Lish, administrator at the Discovery Care Center (an assisted living

facility in Salmon), served with Cope on the City Council.

“He was not only a great friend, but also a mentor. He had a brilliant mind, and a great

memory,” Lish said. “Whether he was working as a vet, or the city council, county

commissioner, or the many state and federal appointments, he was brilliant.”

He served the rural West in many ways most of us were unaware of; he never drew

attention to himself or took credit for his achievements. He accomplished a great deal in

these positions because he was a tremendous strategist.

“It didn’t matter whether he was playing a board game with friends, or working with

people who had opposing philosophies about wolves—trying to find common ground

between them,” Lish said. “Not everybody can find that common ground, but he was often

able to do that because he was such a great strategist.

“He served us well, being able to get folks to agree upon some very controversial issues;

he put forth ideas that were adopted and beneficial to Lemhi County as well as on the

state and federal level. Those of us who were close to him were very proud of those

accomplishments.”

Beyond being a good person to work with, Cope was also a great friend.

“We spent time together enjoying music trivia, sports and games,” Lish said. “He ran the

local Fantasy Football League for almost 20 years. All our fees went into a pot for charity.

We had to pick a charity when we entered, and whoever won (first, second and third

place), the money went to those charities. At one time we had given about $13,000 to

various charities.

“Cope had a clever sense of humor, and this was also where his crafty strategy came into

play. If he even got a hint that you were playing a joke on him, by the time you got it

figured out, the joke would be on you!”

He was a very independent and unique character and never worried about what people

thought of him. When he walked to the courthouse for meetings he was always in bib

overalls and barefoot, and sometimes no shirt, walking with his dog.

“After his passing I thought about many of the times he tried to help us,” Thomas said.

“He was a lot smarter than most of us but never talked down to us, and he respected us.

He was an influential person in my world, as a kid growing up; he was a professional I

looked up to, because of his knowledge, intelligence, work ethic, and the fact he always

had time for everyone. He made a long-lasting impression on me. I looked up to him as a

role model.”

Thomas continued: “He even helped us long distance, when Carolyn and I were ranching

in Mackay, having a wreck with scours and major problems. We called him numerous

times, and he sent vet supplies on the Salmon River Stage that we picked up in Mackay.

He helped us a lot, with many phone calls, and we relied on him. He even came to our

place in Mackay one time when we were in a pinch and couldn’t get a vet. He treated a

bony lump jaw cow for us with intravenous sodium iodide, in an old broke-down facility. He did a lot of work in dilapidated facilities!”

Dr. Cope will be remembered as someone with a lot of gumption.

“This is one of the things I admired about him—how tough he was, and how determined.

Nothing phased him,” Thomas said. “We’ve had him help us do a C-section or deliver a

breech calf in the middle of the night when all we had was a flashlight and no shelter. All

he’d have on was a rubber overall; he’d strip down even in the coldest weather to work

on a cow.”

No matter how hard the work, Cope always kept a positive attitude.

“One thing I always enjoyed about Cope was that no matter how long the day or the job

or how hot or cold the weather, he always had a sense of humor,” Thomas said. “He

loved to tell jokes, and had great stories; working cattle with him was always fun.”

Dr. Cope was a walking encyclopedia of information about all sorts of things.

“For 35 years he hosted the local New Year’s Eve radio program, playing old favorites

and interspersing music with trivia until midnight,” Thomas said. “He knew so much about

each artist and all their songs. Cope had an incredible collection of music and information

in his head about every artist. That made it fun to listen to.”

The past two years, however, Rockwell Smith hosted that program because Cope was in

failing health. The recent one, just three days after Cope’s passing, Rockwell dedicated

the program to Cope, interspersing tidbits of information about his life, throughout the

program.

Even with failing health in recent years (heart problems, pacemaker, ruptured appendix

and peritonitis, prostate cancer) Cope continued to help his clients, putting in long days

pregnancy-checking and all the other jobs they needed him to do. His cancer got

suddenly worse, however, and went into his spine. By January 2022 he had to reluctantly

say no to many friends who needed him, except for advice he could give over the phone,

or at their ranch from his wheelchair as they did the physical part, or working on a small

animal (even young calves) in his home, at a table.

Even after he began to use a wheelchair, Cope continued going to ranches (with help

from people to drive his van and do the physical part of the work) to preg-check cows and

Bangs vaccinate heifers, all through 2022, until a few days before he died. He’d promised

his clients that he would do everything he could for them, for as long as he could, and he

kept that promise.

Chris French visited him a lot at his home.

“At one point he broke into tears and told me he’d known the day was coming that he

wouldn’t be able to continue his work, but didn’t know it would be this way—so crippled,”

French said. “He regretted the fact that people were having to do a lot of things for him,

but I told him he’d served so many people for all those years; these were just small things

we could do for him. Several people had gotten together and built a ramp at his back

door for his wheelchair.”

All those months when he couldn’t get in and out of bed or wheelchair by himself—with

no movement or feeling in his legs—his wife Terrie (with help from her sister and friends)

was his caregiver. He chose to stay home and run the course of those final months

without cancer treatments, and just keep doing what few things he could do. He realized

that any treatment would only be a temporary measure and not a cure, as well as

uncomfortable and costly. So, no hospitals, no treatment.

The incredible thing was how much he was able to continue helping ranchers even after

he needed to use a wheelchair.

“Bart Stephanishen made that possible, taking Cope to ranches in his wheelchair accessible van,” Lish said. “Cope was pretty emotional about his disability, frustrated

about the things he could no longer do, but that side of him was something we never saw

until he became ill. He said the worst thing was that he was unable to be out there

working, where he belonged. It was wonderful that Bart made it possible for him to

continue some aspects of his work.”

Dr. Cope didn’t want a funeral or memorial service. He told Jenelle Thomas that he attended

his dad’s funeral when he was 15, and never went to another, and didn’t want one. But

there will be a wake for him at a later date, for friends to get together and celebrate his

life and share memories and stories about Cope. He would want everyone to have fun

and have a good time.