Dr. James Will, DVM 1960

Well, here I am, Jim Will. A 1960 K-State veterinary medicine grad.

Well, here I am, Jim Will. A 1960 K-State veterinary medicine grad.

I am here at age 92 and telling you of a fabulous career that really came about basically because of my DVM from K-State. As you will see, without the education I had there, none of these things would have happened.

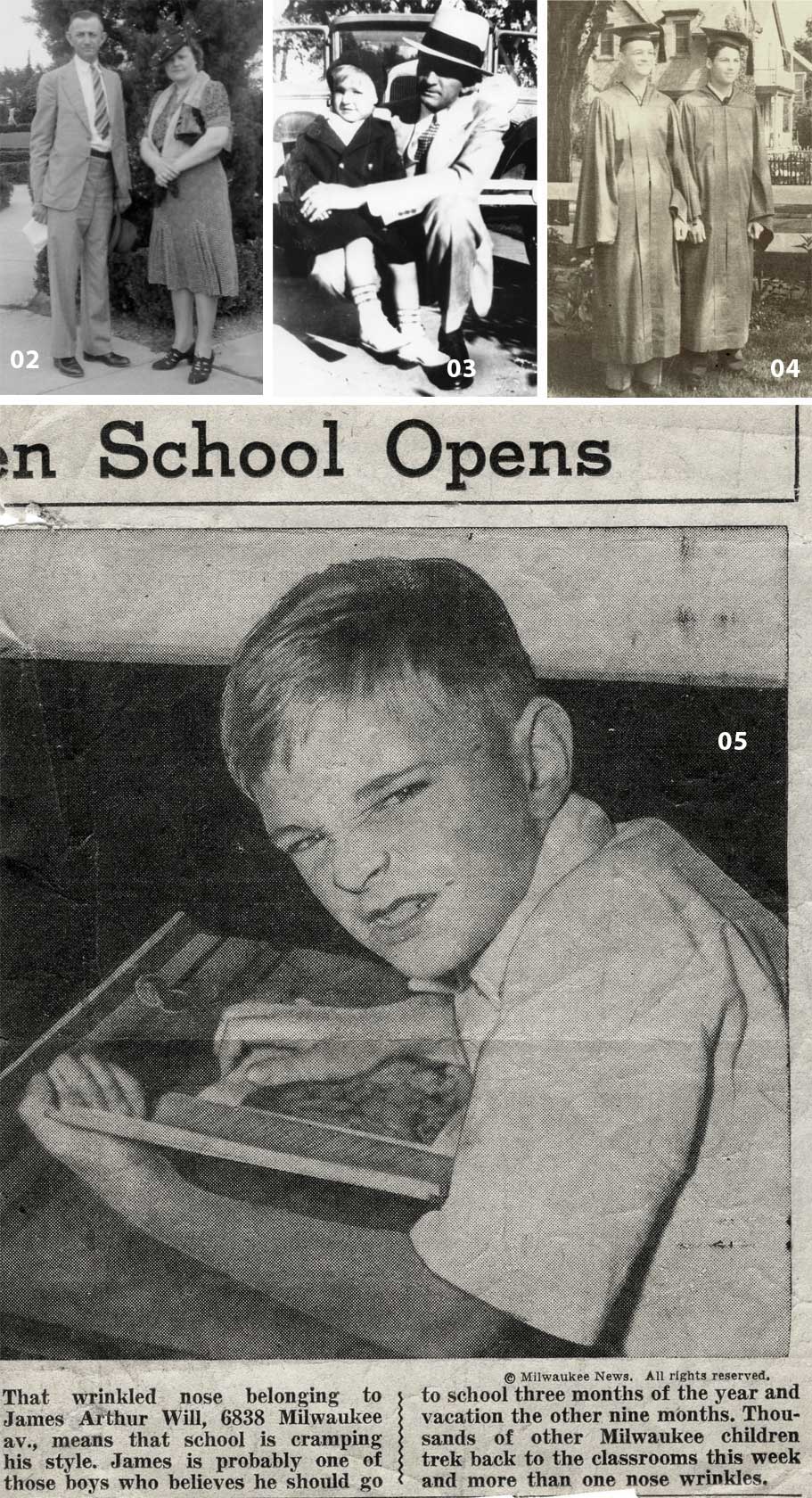

Here is the story of how I got here in the first place. I was a city boy of an upper middle-class family2. Below is a picture of me sitting on my Dad’s lap3. My Dad was rather remarkable in that he had to quit school at age 12 to drive the delivery wagon for the butcher to support the family and went to night school to get through 8th grade. He eventually became the vice president of a growing company. He also had the directorship of a large industry association. My mother during WW1 was a sales representative for a foundry and drove her own car. Then she and sisters had a German bakery.

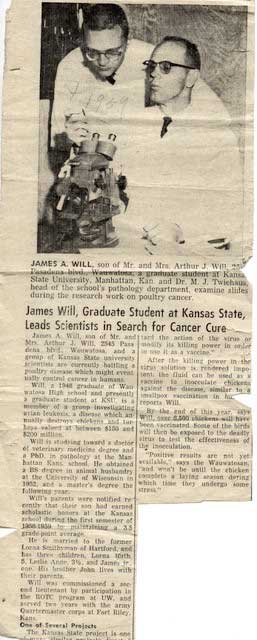

I apparently was a rascal even then5. Here is a picture of my best friend Dr. Jim Van Beckum with me at high school graduation who followed me to veterinary school at Oklahoma4. Very conservative when there was not the animosity there now is, and I was the first to go to college and started in engineering but that lasted only one semester after which I switched to agriculture much to my father’s dismay. Then my MS in Animal Science, the Army and then to KSU.

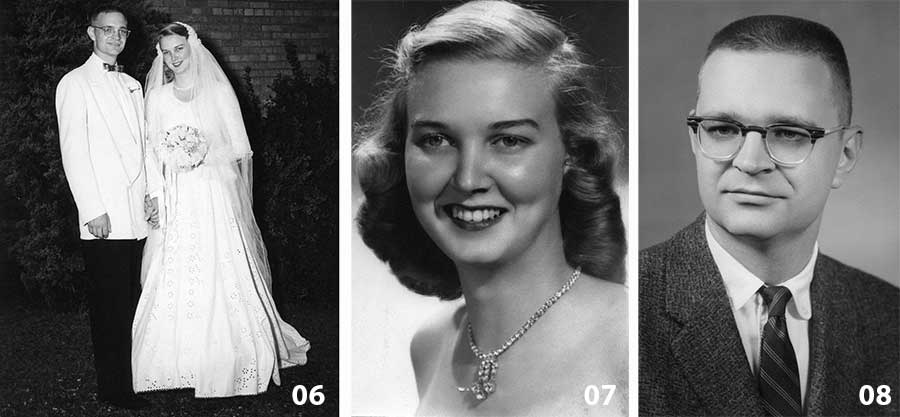

Right before my MS, I met Lorna and we were married in June of 19536,7,8. Next, I was off to the Army from ROTC to Fort Riley, Kansas. I visited K-State with the station veterinarian who encouraged me to go to vet school and that started the path towards my veterinary career.

I was not the usual veterinary student at K-State or for that matter in my previous BS and MS career at the University of Wisconsin.

I want to begin this story with a statement that the basis of my special career in the broad field of medicine began with my special education in veterinary medicine at Kansas State University. Without this especially good veterinary medical education, my career and life would be much different. I came as one of the more mature students in that I had an MS in animal science and and genetics. I was honorably discharged from active duty as a first lieutenant in the US Army in 1956 with two young daughters. A son was born to us in my sophomore year. Another thing that will always distinguish me is that I was interviewed and accepted by an associate dean of the program who after leaving KSU had a practice in Kentucky and was finally found to be a bank robber as well. Find another grad like me!

There are several faculty I wish to mention that had a special impact on my veterinary education at KSU. First, Dr. McLeod. I was working for him when he died. His book on the Bovine Anatomy, second addition, 1958 is still available. Amazing after 64 years! Secondly Dr. McMahon. I was able to do the mock exam in infectious diseases of humans much better than the medical residents. How is that for a comprehensive course in bacteriology/virology of infectious disease? I almost wore out the notes from Dr. Roderick. Interestingly, he was originally from a small town in Wisconsin. I went to his funeral. I was the only person representing K-State. He was important to the world as well since he brought the problem of sweet clover poisoning to the biochemist at UW and this was the discovery of the most used anticoagulant, coumadin, preventing death in humans. The person who most made my career in veterinary medicine what it turned out to be was Marvin Twiehaus. You will see why this was true in the next paragraphs.

In the clinics, there were many who were excellent and I learned equally from most of them but the one who helped me most for my large animal part of my practice, was Dr. E.R. Frank. His book was a great help.

After graduating, I joined a practice in Columbus Wisconsin, 30 miles from the University of Wisconsin in Madison14. I wanted a close connection with the University. My experience at K-State was markedly enhanced by my employment in the Department of Pathology under Marvin Twiehaus and it taught me that I always wanted a close connection with a university. Dr. Twiehaus treated me as part of the team. From doing necropsies for clients in the field to helping with the first diagnosis of anaplasmosis in cattle to assisting staff with their tasks for their research. I did poultry necropsies of avian species at night while my daughters colored on pieces of brown paper on the floor in Dr. John West’s laboratory. I actually became a poultry pathologist consultant for the Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratory and gave a lecture at the Poultry Science Department of the UW. I frequently came home at the end of the day to find a bag of dead birds waiting for me on my porch. Nice, eh?

After graduating, I joined a practice in Columbus Wisconsin, 30 miles from the University of Wisconsin in Madison14. I wanted a close connection with the University. My experience at K-State was markedly enhanced by my employment in the Department of Pathology under Marvin Twiehaus and it taught me that I always wanted a close connection with a university. Dr. Twiehaus treated me as part of the team. From doing necropsies for clients in the field to helping with the first diagnosis of anaplasmosis in cattle to assisting staff with their tasks for their research. I did poultry necropsies of avian species at night while my daughters colored on pieces of brown paper on the floor in Dr. John West’s laboratory. I actually became a poultry pathologist consultant for the Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratory and gave a lecture at the Poultry Science Department of the UW. I frequently came home at the end of the day to find a bag of dead birds waiting for me on my porch. Nice, eh?

Practice had its usual very good things about it, and of course, the not so good ones, too. Somehow, the failures or mistakes stick in your mind more than the good ones. I remember hitting a dog on the road when he went under my front-end biting at my tires and having to stop and carry him into the farmhouse. Then a similar event of getting called out by the police when a dog was hit by a car on the highway and being able to put him down right there to put him out of his pain. Mistakes in practice? Of course, when you try to extract a calf only to find out you have two legs one each of the twins at the same time or trying to be extra safe in after successfully surgically removing a huge pup from a miniature dog only to kill the mother by using an oral-only antibiotic in the wound. These experiences never seem to fade away even after 60 years. Bringing home a new kitten hidden in the pocket of your coveralls, finding a big turtle on the road, putting it in the sandbox where it laid eggs, having a pony in the garage in town are just a few of the good ones.

In this practice, I frequently used my notes from Dr. Roderick’s lectures in pathology. I have to give these lecture notes credit for saving many animals using his lecture material. What else did I do in practice? A partner did most of the cattle work for pregnancy diagnosis; I don’t think I was very good at this compared to him. The third partner in the practice was also a K-State graduate from the end of WWII in an accelerated three-year program.

I did my work in all species and made diagnoses of many problems even being especially contacted out of my practice area to deal with a pneumonia problem in a 200 beef steer herd fed on the now discredited use of adding of low doses of antibiotics in the feed. I spent a week of running all the animals through a chute to temp them more than once to give IV antibiotics and saved them all. One night I was called out to a farm where the shelled corn grain bin burst into the dairy cow barnyard and twelve cows had already bloated. I worked as fast as I could to put trocars into the rumens and injected the antibloat. I saved them all when they were in very bad shape, some down, when I arrived. In my equine adventures, I delivered twins successfully and saved a horse that was down after a prolapsed uterus. I had learned from Kansas clinics that giving 500cc in a large animal was not up to par and I gave her 2-3 liters and the mare got up and was fine. I also operated on the world champion Morgan horse to prevent him from locking up in his final stance by cutting a lateral ligament. I made a diagnosis in a field necropsy of a cow that the State diagnosticians could not figure out that was poisoning from the fly spray containing a mistaken ingredient. The State Crime Lab made the diagnosis and the farmer was given a large settlement. I had seen the same lesions at a pig farm in Kansas that Dr. Twiehaus sent me out to, to figure out the problem. During this time in Columbus, we built a new modern veterinary hospital that still stands with renovations since it is now a strictly small animal practice. Dairy farms went from 800 clients when I started to 500 when I left four years later. This was the great switch from dairying to just field crops that now seems a disaster.

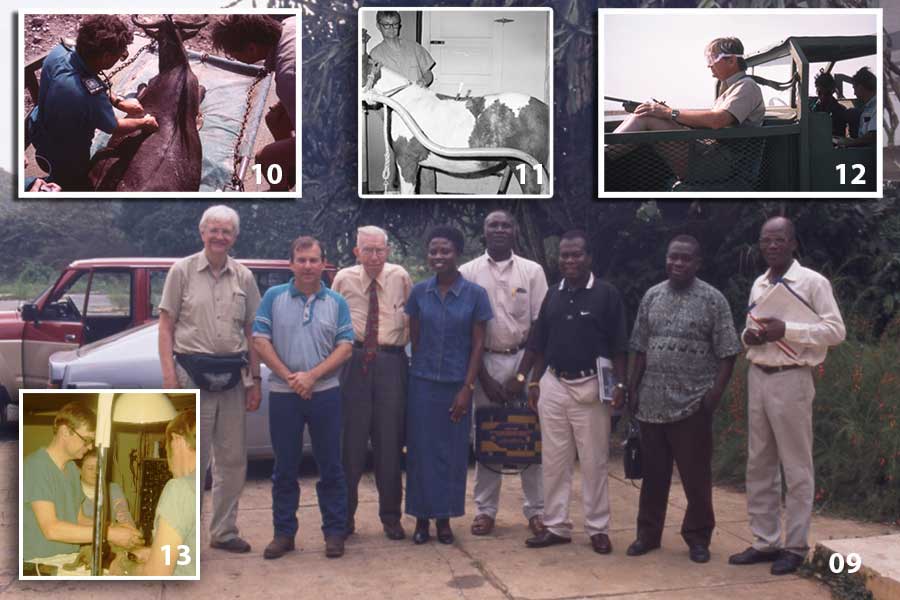

All in all, you can see that my four years in practice was a very valuable experience, but my life certainly changed over the next four years. I was very upset when the elderly retired former owner of our practice who worked for us in the office had a heart attack maybe after helping me trim a donkey’s feet. I decided it was time for me to get into academic medicine once more. I went to the University of Wisconsin Department of Veterinary Science and saw Dr. Carl Olson who was the pathologist. I was interested in physiology and particularly cardiovascular physiology, but he was a contact I knew. There were no physiologists in Veterinary Science at that time. He contacted the Medical School cardiologist who was responsible for the resident program. I applied for and received an NIH fellowship and started my career in comparative cardiology. First of all, I had to take several Medical School courses and then I was accepted as a somewhat confined duty resident. My assignment was to immediately become a member of the cardiac catheterization team under Dr. George Rowe. Most of the patients were persons who had scarlet fever before antibiotics and thus had valve problems. Six-thirty AM Monday through Friday in the cardiac catheterization lab with a lead apron after previously visiting and examining all patients for the week and Saturday morning for the conference at 7:30. A remarkable assignment for a veterinarian. Impossible today I believe because of all of the regulations and insurance requirements. I did this for 1.5 years and then was given a station in the pediatric cardiology clinic for another six months. All this time I was doing my research for my PhD in calves. I also did other research with my graduate students13. I learned to do catheterizations in awake standing calves to begin defining the effects of compounds on the circulation of these animals. I was officed in the Medical School with two physicians who were doing their own research and I became a good resource for them to test their hypotheses in animals. One outcome was the development a heated coil to damage a coronary artery in an awake animal to form clots mimicking a clotted coronary artery in man.

In 1968, I received my PhD and a joint appointment as an assistant professor in veterinary science in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and Cardiology in the Department of Medicine of the Medical School11. Different from now, this was a time to take your time, explore new ideas and then try to get funding. At the same time, there was a Swiss pharmaceutical company that developed a diet drug that was apparently causing primary pulmonary hypertension in young women in Germany, Switzerland and Austria where it was distributed. Dr. Rowe wasn’t interested and suggested me. This was career changing again. The parent company was Johnson and Johnson. I was provided funding to test the drug in animals to see if the drug caused a persistent increase in pulmonary artery pressure if taken daily. My team and I did this in beagle dogs. The increase in pulmonary artery pressure did not persist. Here I again had a new challenge in my career to study the pulmonary circulation. To learn more, I applied for a special NIH postdoctoral fellowship to study with a group at the Liverpool Medical School where the pathologist there was the leading person in the pathology of the pulmonary circulation. I received the one-year award. My work with the beagles followed me and I was constantly on the go while in England to testify in a court in Bern Switzerland or to meet with a physician’s family in Germany whose daughter was dying of primary pulmonary hypertension.

I became J&J’s consultant on primary pulmonary hypertension. With it I became an honorary staff member at the German Experimental Cardiology Research Center in Bad Nauheim, Germany where I spent many times doing research there in animals and man with this distinguished group. This group had a connection with J&J because the director at the Center was someone who had fled East Germany and was formerly at Janssen Pharmaceuticals in Belgium. At this time, I also became a much broader consultant for 10 years at Janssen and to Dr. Paul Janssen, the President and CEO. During this time, I had many responsibilities with Janssen. One of them was unusual but very interesting. I went to Etosha National Park in Namibia, Africa where Janssen was evaluating various new modifications of Fentanyl, their drug originally. One of the photographs12 shows me ready to dart an animal and then actually teaching the veterinarian how to do a puncture of the aorta in a wildebeest for direct sampling of arterial blood10. I had published this technique. This was done in wildebeest by the distinguished veterinary director, Dr Ian Hofmeier.

My obligations at UW were not forgotten. I applied for and got an NIH grant to research the pulmonary circulation using cattle at high altitude in association with Dr. Robert Grover at the General Hospital in Denver. Our model of human disease was brisket disease, a problem with cattle at high altitude. We personally physically built a laboratory at Climax, Colorado, and did some work in the hospital in Leadville. We broadened the research to other species including the llama. In Madison, I continued my career in veterinary medicine. I became chairman of UW Veterinary Science and then President of the American Association of Veterinary Colleges. On campus I was the Chairman of the Biological Division which ruled on promotions with tenure for all persons in biology and medicine and on development of all courses. I seemed to be leading many lives at the same time. I was also appointed the director of the new Research Animal Resources Center with only a few veterinarians to take care of the very extensive research animal use. In addition to the Madison campus, I was responsible for the welfare of all 26 university UW System campuses large and small. Fortunately, only about 15 had courses or teaching or research using animals. I divided these up between my three veterinarians and myself for the annual inspection visits. I had the job for 10 years.

I also became an adjunct professor in anesthesiology in the Medical and Public Health School for 10 years and later in Surgery as well. In anesthesiology, I set up new laboratories to help young faculty do research so they could attain tenure.

About this time I held an international meeting on the pulmonary circulation at the UW called, “The Pulmonary Circulation in Health and Disease." A book was published from this. I was on the organizing committee for the European Cardiology meeting about then.

My association with Janssen Pharmaceuticals was a wonderful education. When there, I was able to sit in with Dr. Janssen as he reviewed the screening of the compounds from the previous day. He was an MD and a PhD in pharmaceutical chemistry as well as being president and chairman of the board of the company. They were screening 3,500 compounds per year as opposed to a few hundred at most in other companies. I learned at the knee of the most talented head of a pharmaceutical company in the world.

Things changed when Dr. Paul was required to retire and the after a year or so, I became a consultant to the Upjohn company in both their human and animal divisions and a special consultant position to Dr. Ted Cooper who was the former US Surgeon General and was then the chairman of the Board at Upjohn.

In addition, I was consultant to one of the largest law firms in Washington, for problems with tobacco and human health.

During this time, I was also asked to be on the World Health Organization committee on the pulmonary circulation and to author the chapter on the pharmacology of the pulmonary circulation, which was a huge honor for me.

I also became a consultant to other projects in World Health. I worked as an advisor for several projects around the world.

The most interesting was a trip to Ghana. This project was to try to develop concepts for developing community outhouses rather than the typical individual in-home units and to develop better health facilities09. The leader of our group was Dr. Lawrence Pratt who was one of the founders of the medical school in Vietnam and had a distinguished career in medicine. He was 91years old. My responsibility was to see how animal and human waste disposal could be integrated.

My family was growing and doing well in college and in their professions. Daughter Lorna was a nurse in Boston and Seattle and is now working for the WI Dept of Public Health. Leslie was a chair at Harvard and is now Chair of Orthodontics and an Associate Dean at Boston University; James taught at the Burnley College of Horticulture in Melbourne, Australia and is now creating native plant landscapes in Townsville, Australia. We have two grandchildren; Leslie’s children. Daughter is Lindsay, an endocrine surgeon at Temple University, Andrew is a director of a large multiunit real estate corporation in California. We also have two great grandsons. Grandchildren each have one15, 16.

At this point, it is necessary to make sure, my wife Lorna is honored. Even though she was employed as a registered hospital dietitian in hospitals and nursing homes she was also a federal veteran through her Public Health Service experience. She kept the family going while I was running all over the world. She is still providing a family foundation. Our marriage still exists after 70 years.

Eventually, I retired from the UW in 2000. I became an Emeritus professor and an adjunct professor in Biomedical Engineering at the College of Engineering to bring principles of the medical element into their training. A former graduate student, whose committee I was on, is now president of the Carnegie Mellon University in Bangkok. In 2001 I went to Khon Kaen, Thailand where my former graduate student, Dr. Nee Trakranrungsie, was an assistant professor in physiology That visit began a new career in 2001. I evaluated research programs in all of their Faculties (colleges) to try to develop some collaborations between the UW and them. The veterinary connection didn’t take, but the Medical Faculty did. I was invited back the next year and then was made a Visiting Professor in 2004. A young couple from there came to our UW Cancer Research Center for a year. They are now collaborators for our Carbone Cancer Center. She has received many honors in cancer research and their 17-year-old son, born here, just presented his own math research at an international math meeting and won an award there. He now has two publications in international journals. Now he is now a freshman in computer sciences at UW and his mother is a collaborator at our Carbone Cancer Center.

Somewhere in between all of the above things, I was in seven countries in Africa for various reasons including giving a lecture in an elementary school in Soweto, South Africa. One trip was special. I went to Ghana with the physician who started the medical school in Vietnam, Dr. Lawrence Pratt. If anyone in curious about him I am sure there is something on line. We tried to develop plans for them to develop a better way to take care of their human waste. We saw patients there with Mycobacterium ulcerans in which if the lump was not removed in the early stage, the limb would have to be amputated. Interestingly, the lesions were mainly on children. Infection seemed to be from the river water where the children went to fill the pails with water; the only source of water in this village. This was an incredible experience.

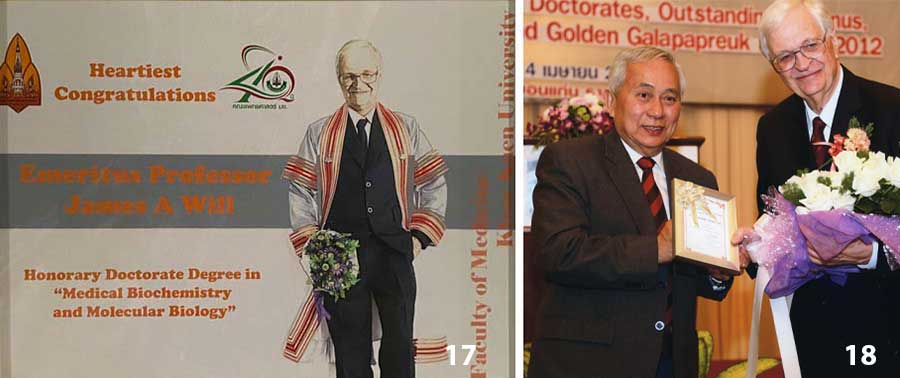

Here is the end of the story of my career. I have a book and 135+ edited publications in which I actually participated in the research. I am still working as senior (in both ways!) editor for the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, my 22nd anniversary year of association. I was honored in a meeting of the southeast Asian meeting research organization18. In 2012, I was honored by the University with an honorary PhD presented by the Crown Princess of Thailand17. I am also a Life Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine, London.

I believe that my education at KSU in many classes like the bacteriology, pathology, good clinical training and opportunities given to me by Dr. Marvin Twiehaus provided me with special opportunities to be especially successful in veterinary medicine and the world of medicine.

During my time at KSU I also was a member of the Army reserve, became a Captain, and eventually retired at this rank.

So here we are at 92 years old, a 1960 graduate of KSU veterinary medicine with a wonderful family and fantastic career fostered by my KSU veterinary medicine education.